Birmingham (The Conversation): Most people will have heard the term "man flu", which refers to men's perceived tendency to exaggerate the severity of a cold or a similar minor ailment.

What most people may not know is that, generally speaking, women mount stronger immune responses to infections than men.

Men are more susceptible to infections from, for example, HIV, hepatitis B, and Plasmodium falciparum (the parasite responsible for malaria).

They can also have more severe symptoms, with evidence showing they're more likely to be admitted to hospital when infected with hepatitis B, tuberculosis, and Campylobacter jejuni (a bacteria that causes gastroenteritis), among others.

While this may be positive for women in some respects, it also means women are at greater risk of developing chronic diseases driven by the immune system, known as immune-mediated inflammatory diseases.

Here we will explore how biological factors influence immune differences between the sexes and how this affects women's health.

While we acknowledge that both sex and gender may affect immune responses, this article will focus on biological sex rather than gender.

Battle of the sexes

There are differences between the sexes at every stage of the immune response, from the number of immune cells, to their degree of activation (how ready they are to respond to a challenge), and beyond.

However, the story is more complicated than that. Our immune system evolves throughout our lives, learning from past experiences, but also responding to the physiological challenges of getting older.

As a result, sex differences in the immune system can be seen from birth through puberty into adulthood and old age.

Why do these differences occur? The first part of answering this question involves the X chromosome. Females have two X chromosomes, while males have one X and one Y chromosome. The X chromosome contains the largest number of immune-related genes.

The X chromosome also has around 118 genes from a gene family that are able to stop the expression of other genes, or change how proteins are made, including those required for immunity.

These gene-protein regulators are known as microRNA, and there are only two microRNA genes on the Y chromosome.

The X chromosome has more genes overall (around 900) than the Y chromosome (around 55), so female cells have evolved to switch off one of their X chromosomes. This is not like turning off a light switch, but more like using a dimmer.

Around 15-25 per cent of genes on the silenced X chromosome are expressed at any given moment in any given cell.

This means female cells can often express more immune-related genes and gene-protein regulators than males. This generally means a faster clearance of pathogens in females than males.

Second, men and women have varying levels of different sex hormones.

Progesterone and testosterone are broadly considered to limit immune responses.

While both hormones are produced by males and females, progesterone is found at higher concentrations in non-menopausal women than men, and testosterone is much higher in men than women.

The role of oestrogen, one of the main female sex hormones, is more complicated. Although generally oestrogen enhances immune responses, its levels vary during the menstrual cycle, are high in pregnancy and low after menopause.

Due in part to these genetic and hormonal factors, pregnancy and the years following are associated with heightened immune responses to external challenges such as infection.

This has been regarded as an evolutionary feature, protecting women and their unborn children during pregnancy and enhancing the mother's survival throughout the child-rearing years, ultimately ensuring the survival of the population.

We also see this pattern in other species including insects, lizards, birds and mammals.

What does this all mean?

With women's heightened immune responses to infections comes an increased risk of certain diseases and prolonged immune responses after infections.

An estimated 75-80 per cent of all immune-mediated inflammatory diseases occur in females.

Diseases more common in women include multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, Sjogren's syndrome, and thyroid disorders such as Graves disease.

In these diseases, the immune system is continuously fighting against what it sees as a foreign agent.

However, often this perceived threat is not a foreign agent, but cells or tissues from the host. This leads to tissue damage, pain and immobility.

Women are also prone to chronic inflammation following infection.

For example, after infections with Epstein Barr virus or Lyme disease, they may go on to develop chronic fatigue syndrome, another condition that affects more women than men.

This is one possible explanation for the heightened risk among pre-menopausal women of developing long COVID following infection with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID.

Research has also revealed the presence of auto-antibodies (antibodies that attack the host) in patients with long COVID, suggesting it might be an autoimmune disease.

As women are more susceptible to autoimmune conditions, this could potentially explain the sex bias seen.

However, the exact causes of long COVID, and the reason women may be at greater risk, are yet to be defined.

This paints a bleak picture, but it's not all bad news. Women typically mount better vaccine responses to several common infections (for example, influenza, measles, mumps, rubella, hepatitis A and B), producing higher antibody levels than men.

One study showed that women vaccinated with half a dose of flu vaccine produced the same amount of antibodies compared to men vaccinated with a full dose.

However, these responses decline as women age, and particularly after menopause.

All of this shows it's vital to consider sex when designing studies examining the immune system and treating patients with immune-related diseases.

Let the Truth be known. If you read VB and like VB, please be a VB Supporter and Help us deliver the Truth to one and all.

Ottawa (PTI): Three Indian nationals have been arrested by Canadian police on an anti-extortion patrol and charged after bullets were fired at a home.

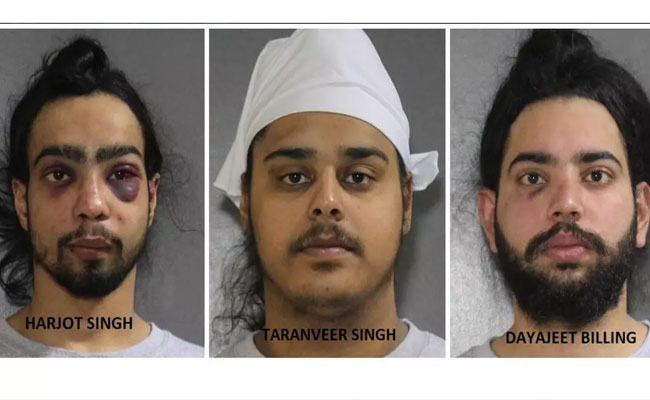

Harjot Singh (21), Taranveer Singh (19) and Dayajeet Singh Billing (21) face one count each of discharging a firearm, and all have been remanded in custody until Thursday, the Surrey Police Service (SPS) said in a statement on Monday.

The suspects were arrested by patrol officers after an early morning report of shots fired and a small fire outside a home in Surrey's Crescent Beach neighbourhood, the LakelandToday reported.

On February 1, 2026, the SPS members were patrolling in Surrey’s Crescent Beach neighbourhood when reports came in of shots being fired and a small fire outside a residence near Crescent Road and 132 Street.

The three accused were arrested by SPS officers a short time later, the statement said.

SPS’s Major Crime Section took over the investigation, and the three men have now been charged with Criminal Code offences, it said.

All three have been charged with one count each of discharging a firearm into a place contrary to section 244.2(1)(a) of the Criminal Code.

The investigation is ongoing, and additional charges may be forthcoming. All three have been remanded in custody until February 5, 2026.

The SPS has confirmed they are all foreign nationals and has engaged the Canada Border Services Agency, it said.

One of the suspects suffered injuries, including two black eyes, the media report said.

Surrey police Staff Sgt. Lindsey Houghton said on Monday that the suspect had refused to comply with instructions to get out of the ride-share vehicle and started to "actively resist."

"As we were trained, he was taken to the ground and safely handcuffed," said Houghton.

A second suspect with a black eye was also injured in the arrest after refusing to comply, Houghton said.

The arresting officers were part of Project Assurance, an initiative that patrols neighbourhoods that have been targeted by extortion violence.

Houghton said the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) is also involved because the men are foreign nationals, and the trio may face additional charges.

It's not clear if the men are in the country on tourist visas, a study permit, or a work permit, but Houghton said CBSA has started its own investigation into the men's status.

Surrey has seen a number of shootings at homes and businesses over the last several months, but there's been an escalation since the new year.