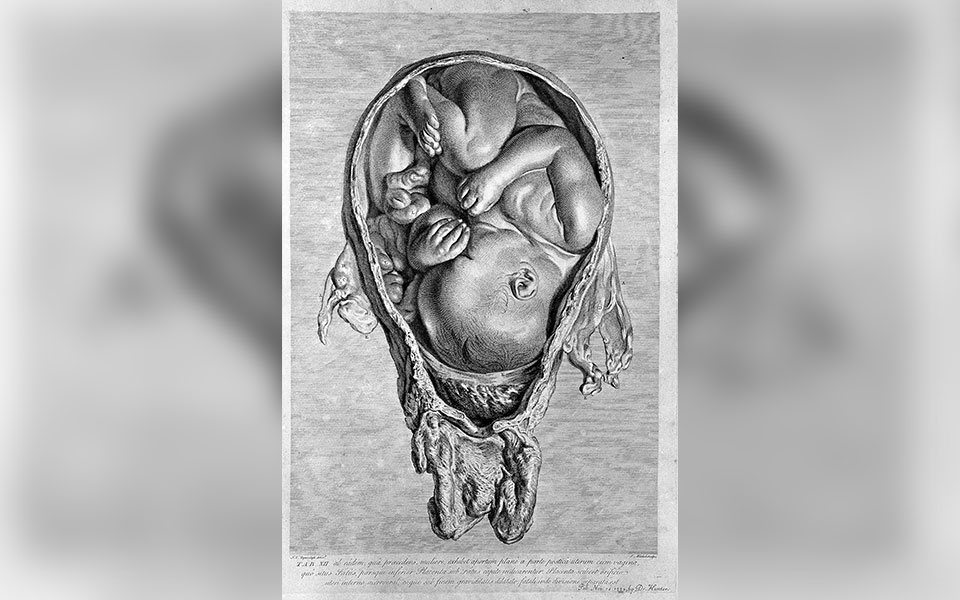

New Delhi: A woman working as Office Assistant in the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) here alleged on Saturday she was brutally assaulted by husband and in-laws when she was pregnant after she refused to abort her female foetus, police said.

The woman, 42, a resident of Sector 49, Gurugram, got married to a Delhi-based doctor, Rajnish Gulati on July 21, 2016. Gulati is associated with Mudit Vishwakarma Hospital and resides in West Patel Nagar, police said.

"The woman in her complaint to police said Gulati, his sister Amita, his uncle Sushil Kumar Nagrath and her mother-in-law Sarla Gulati dragged her from their house after she refused to abort her female foetus, in February this year," the FIR said.

"When I tried to enter my her in-laws' house, my mother-in-law beat her. Later, I complained to Delhi Police but no action was taken against my husband and in-laws," the victim told IANS.

She also alleged in her complaint to Delhi Police Commissioner Amulya Patnaik and Assistant Commissioner of Police (ACP) Rohit Rajbir Singh that Station House Officer (SHO), Pramod Kumar Joshi and a Sub Inspector, Devender, posted in Patel Nagar Police Station traumatised her on many occasion and threatened to fabricate her in wrong cases if she does not take her complaint back.

She also alleged that SHO Joshi, on April 1, 2017, forced her to sit in police station for over six hours and did not let her drink water and eat food, even though she was pregnant.

Her husband also beat her inside the police station. The repeated assault and trauma eventually led to miscarriage.

She later approached Tis Hazari Court against them. During counselling in the court, her husband assured that the matter would be sorted out peacefully and also requested her to issue a written statement that she would not go for any legal action against him and his family members.

He took the victim to his residence but after a week, threw her out from house. The woman made a fresh complaint on Monday (December 25) against her in-laws and SHO Joshi, and sought action.

ACP Rohit Rajbir Singh told IANS that he has received a complaint regarding cruelty on the woman by her husband and in-laws.

"We are examining the matter," the police officer said.

Let the Truth be known. If you read VB and like VB, please be a VB Supporter and Help us deliver the Truth to one and all.

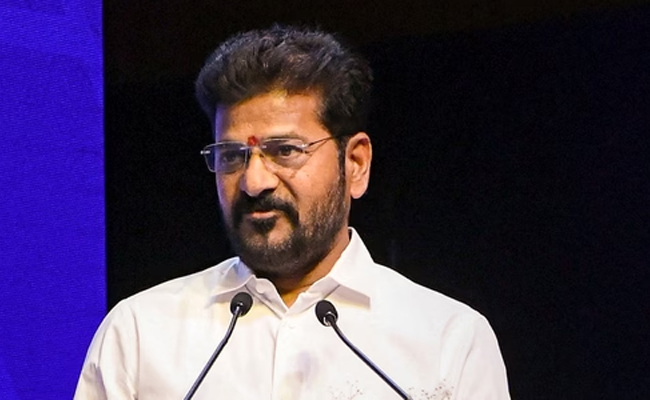

Hyderabad (PTI): Telangana Chief Minister A Revanth Reddy met Union Home Minister Amit Shah in Delhi on Wednesday night and urged him to increase the sanctioned strength of IPS officers to the state in view of its growing administrative and security needs.

The two leaders also discussed the recent surrender of several senior Maoist leaders before the Telangana Police and other issues.

"During the meeting, the two leaders discussed the issue of Maoist surrenders and their rehabilitation. The chief minister informed Shah that significant improvements in policing have taken place in Telangana over the past two years," an official release here said.

Highlighting that 591 Maoists have laid down their arms and joined the mainstream of society during this period, the chief minister said the state government was providing them compensation and rehabilitation assistance as per the rules.

He requested the Union home minister to extend financial support from the central government for development works in the backward regions of the state.

Reddy also urged Shah to increase the sanctioned strength of IPS officers to the state from 83 to 105 in line with the state's growing administrative and security needs, the statement said.

The first cadre review after the formation of Telangana was conducted in 2016, while the next review, due in 2021, was delayed and finally carried out in 2025. Even then, only seven additional IPS officers were allocated to the state, the chief minister informed Shah and requested that the third cadre review be conducted in 2026 as per the schedule.

Reddy explained that Telangana, like the rest of the country, is facing several modern challenges, including cybercrime, drug trafficking, white-collar crimes, and other emerging security threats.

He highlighted the reorganisation of the Hyderabad, Cyberabad, and Malkajgiri Police Commissionerates, the proposed formation of the Future City Commissionerate and the rapidly growing population in Hyderabad to underline the increasing administrative requirements of the state.