Mangaluru: Fresh details from the chargesheet in the April lynching of 38-year-old Ashraf, a mentally ill man from Kerala, have put the spotlight back on the role of Ravindra Nayak, husband of former BJP corporator Sangeetha Nayak in instigating the mob. The revelations have raised serious questions on the conduct of the Mangaluru City Police, who initially dismissed his involvement despite statements from all 21 accused pointing to his active role.

The case, which took place during a cricket tournament in Kudupu, had sparked communal tensions after some participants alleged that Ashraf shouted “Pakistan Zindabad” before being beaten to death. However, rights groups and several villagers have contested this narrative, saying Ashraf appeared mentally unstable and was targeted following a minor altercation.

Police Commissioner’s Statement vs Chargesheet Evidence

On April 30, just a day after the statements were recorded, the then Mangaluru Police Commissioner Anupam Agrawal told The News Minute that “nobody had complained” against Ravindra Nayak. This public denial came despite the fact that, according to the chargesheet, all accused had spoken in detail about his involvement during their interrogation on April 29.

The statements, now part of the court record, paint a consistent picture Nayak was present during the assault, dismissed attempts by some players to stop the beating, and openly encouraged the mob to “beat him to death” because he allegedly shouted pro-Pakistan slogans.

What the Accused Told the Police

In their accounts, several accused said that after Ashraf was first assaulted, a few members of the Konguru cricket team, including Deepak, urged others to stop. They pointed out that Ashraf seemed mentally unstable and had already suffered serious injuries, suggesting that he should be taken to hospital to avoid trouble.

However, according to the statements, Nayak, referred to as “Ravi anna” along with Manjunath and Devadas, overruled them. He allegedly told the group:

“If you simply let go of someone who comes into our area shouting ‘Pakistan, Pakistan,’ tomorrow more people will come and do the same. We will question him properly, then inform the police, and will make all arrangements so that none of us gets into trouble.”

The chargesheet quotes multiple accused as saying that Nayak’s words emboldened the crowd. Others, including Kishore Kumar and Anil Kudupu, reportedly supported him and urged, “Don’t let this sulemaga(b@st@rd) go. Beat him to death right here.”

Cover-Up and Instructions to Stay Silent

The statements also reveal that Nayak played a role after the assault in trying to cover up the incident. Another accused Devadas and Nayak allegedly told the group:

“What’s done is done. Now, we should all act as if we know nothing. Do not tell anyone about what happened. If the police come and ask, say you know nothing. If anyone opens their mouth, all of us will get into trouble. If the police call us for inquiry, inform us we’ll all go together. At the station, no one else should speak, I will do the talking. If no one reveals what happened, the police will file a C report and close the case.”

This assurance, according to the accused, gave them the confidence to stay quiet in the initial days after the killing.

Night Meeting at Nayak’s House

An additional statement from accused Sridutt adds another layer to the case. He recounted that later that night, he and fellow accused Dixit met a friend who they informed about Nayak’s presence at the scene. Following this, they went to Nayak’s house in Kudupu, where he reportedly told them:

“Nothing will happen to the people. Don’t be afraid. If no one speaks up, it will be over. I will take care of everything.”

From ‘Unnatural Death’ to Murder Case

Initially, the police registered the case as an “unnatural death” and claimed Ashraf had fallen while drunk. It was only after public outrage, media coverage, and pressure from rights groups that it was registered as a murder case. The post-mortem report that came-out on July 25, confirmed 35 external injuries, all caused by blunt force impact. Ashraf had bruises, cuts, tramline marks, and internal bleeding in multiple parts of his body, including his head and genitals.

Rights groups have alleged that the “Pakistan Zindabad” claim was fabricated to justify the brutal assault. The fact-finding report ‘Lost Fraternity: A Mob Lynching in Broad Daylight’ criticised the authorities for failing to act promptly and for shielding those politically connected.

Questions Over Police Integrity

The fact that the then police commissioner Anupam Agrawal denied Nayak’s involvement even when statements against him were already recorded raises troubling questions about whether the investigation was influenced to protect him. The delay in arresting key accused more than 48 hours after the lynching also points to lapses in handling the case.

After the transfer of the then Mangaluru Police Commissioner, Sudheer Kumar Reddy took charge, giving fresh momentum to the investigation into Ashraf’s murder and ensuring proper arguments were presented in court against the accused. However, on the question of Ravindra Nayak’s role, the new commissioner too maintained that there was no evidence against him. He went a step further by summoning to the police station those who posted on social media asking why Nayak had not been arrested, warning them that unless they had evidence against him, they should refrain from making such posts.

Activists say the chargesheet exposes a pattern where the police tried to control the narrative, initially downplaying the incident, pushing a communal angle, and avoiding action against a politically influential figure.

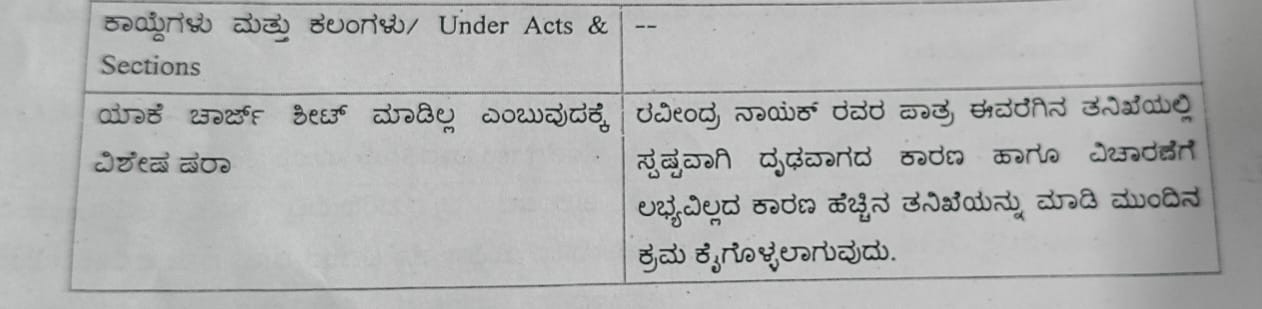

In the chargesheet, police have stated that since Ravindra Nayak’s role has not been “clearly established” in the investigation so far and he has not been available for questioning, he has not been named as an accused at this stage. The document notes that further investigation will be carried out to verify his involvement, and any necessary action will be taken based on the findings.

For now, Nayak remains named in the chargesheet only based on consistent testimonies from all accused, but whether this translates into accountability will depend on how the case proceeds in court.

Let the Truth be known. If you read VB and like VB, please be a VB Supporter and Help us deliver the Truth to one and all.

When you go to a shop and the shopkeeper says, “Price badh gaya hai, naya tax laga hai,” you usually do only one thing — you sigh and pay more. You do not argue with the government; you simply adjust your household budget. That is exactly what is happening in the United States right now. And when prices and taxes change in America, the effect does not stay there. It slowly travels across oceans and reaches India too.

On 21 February, American President Donald Trump announced a new 15% import tax on almost all goods entering the US from other countries. An import tax, also called a tariff, is simply extra money charged when a product crosses the border — like a gate fee. A T-shirt from Tiruppur, a medicine from Hyderabad, or an electronic item from China — if it wants to enter the US market, it must now pay 15% extra. Companies usually pass this extra cost to customers. So in the end, it is the ordinary American buyer in a supermarket who pays more.

This 15% tax did not come out of nowhere. Just one day earlier, on 20 February, Trump had announced a 10% global import tax. Before that, he had introduced even higher tariffs, which the US Supreme Court struck down. The court said he was misusing a law called the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA). That law is meant for genuine emergencies — like dealing with hostile nations or blocking dangerous financial flows — not for imposing wide import taxes on almost the entire world. In simple terms, the court said normal trade cannot be labelled an emergency just to collect extra tax.

So Trump turned to another legal option: Section 122 of the Trade Act of 1974. This rarely used law allows a president to impose temporary import surcharges when there is a serious trade imbalance. It permits tariffs of up to 15%, but only for 150 days — roughly five months. That is why it feels like a 150-day fuse. The law was originally designed for situations when the US was buying far more from other countries than it was selling to them — what economists call a trade deficit. Trump argues that America’s large and long-standing trade deficit justifies this step.

However, legal experts are divided. Some believe today’s trade deficit may not fully match the conditions envisioned when Section 122 was written decades ago. That means the new tariff could also face legal challenges. But until any court decision changes it, the 15% tariff is active.

The numbers explain the shift clearly. Before the Supreme Court struck down the earlier tariffs, the average import tax in America had risen to about 16%. After the court ruling, it fell sharply to around 9%. Now, with the new 15% global tariff, analysts expect the overall average to settle somewhere between 13% and 14%. In simple words, tariffs are lower than last year’s peak but higher than they were just days ago. They have not returned to old normal levels.

Why does this matter for India? Because the US is one of India’s largest export markets. India sends medicines, IT services, textiles, gems and jewellery, engineering goods, and auto components to America. If a 15% tariff is applied, Indian exporters face a difficult choice. Either they absorb the extra cost and accept lower profits, or they raise prices and risk losing customers. Lower profits often mean slower hiring, reduced investment, and cautious spending. Trade policy may look distant, but it quietly influences jobs and incomes here at home.

Earlier discussions between India and the US involved a possible 18% tariff structure. On paper, 15% seems better. But the earlier framework was clearer and more stable. The new 15% tariff comes with a 150-day time limit and the possibility of court battles. In business, predictability is often more valuable than small numerical advantages. Companies can manage higher costs if they are stable; uncertainty is harder to manage.

There are some exemptions. Certain medicines, critical minerals, defence-related goods, and some products from Canada and Mexico are excluded under special agreements. So the rule is not entirely universal. But for a large share of imports — including many low-cost online products — the 15% tariff applies.

Another important change concerns the “de minimis” rule. Earlier, goods valued at 800 dollars or less could enter the US without paying import tax. This allowed online sellers and platforms to ship small packages directly to American consumers easily. That benefit is now effectively suspended. The administration has confirmed that even these small parcels will face the new tariff. In addition, a major tax bill passed recently will permanently phase out the de minimis system for commercial shipments by around mid-2027.

Trump has also mentioned other legal tools. Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 allows tariffs on industries linked to national security, such as steel, aluminium, and automobiles. Some of these sectors already face tariffs of 25% to 50%. The new 15% global tariff will not be added on top of those existing Section 232 tariffs. Another option, Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974, allows long-term tariffs on countries accused of unfair trade practices. However, both Section 232 and Section 301 require detailed investigations and take months to implement. Section 122, in contrast, acts quickly.

What happens on the ground? Studies from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York suggest that most of the cost of earlier tariffs was ultimately paid by American companies and consumers. When importers pay more, they try to pass that cost along the supply chain. This leads to higher prices for goods like home appliances, furniture, and vehicles. Some companies delay hiring or postpone expansion plans.

Not everyone loses. Certain domestic industries benefit from protection. For example, US shrimp fishermen have said that higher tariffs on imported shrimp made their local products more competitive. In trade policy, one sector’s protection often means another sector’s higher cost.

The broader issue is stability. Tariffs are powerful economic tools. But when they change frequently or face repeated legal challenges, businesses struggle to plan. They hesitate to invest, hire, or sign long-term contracts. Uncertainty itself becomes a cost.

Trump believes America has been disadvantaged in global trade and wants to strengthen domestic manufacturing. Many supporters agree that protecting key industries and reducing dependence on foreign supply chains is important. The debate is less about the objective and more about the method. A major trading nation needs policies that are clear, predictable, and legally sound.

Trade policy may appear technical, but it has everyday consequences. It can influence the price of shoes in a shop, the hiring decision of a factory in Chennai, or the expansion plan of an exporter in Gujarat.

Trump’s 15% global tariff and its 150-day timeline are not just political headlines. They represent a shift in how trade costs are distributed across countries and consumers. And in global economics, the final bill almost always reaches ordinary people — whether they wrote the rules or not.

(Girish Linganna is an award-winning science communicator and a Defence, Aerospace & Geopolitical Analyst. He is the Managing Director of ADD Engineering Components India Pvt. Ltd., a subsidiary of ADD Engineering GmbH, Germany.)

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect the views, policies, or position of the publication, its editors, or its management. The publication is not responsible for the accuracy of any information, statements, or opinions presented in this piece.