Paris: The U.N. says it's urgent to get kids back to schools after months-long coronavirus lockdowns, but with the virus still raging in parts of the United States and resurging in countries from South Korea to France, Spain and Britain, medical authorities are urging caution.

Governments are taking different strategies toward the new school year, depending on how many infections they're seeing, the state of their health care systems and political considerations.

Here's a look at how some countries are handling reopening schools amid the pandemic: UNITED STATES

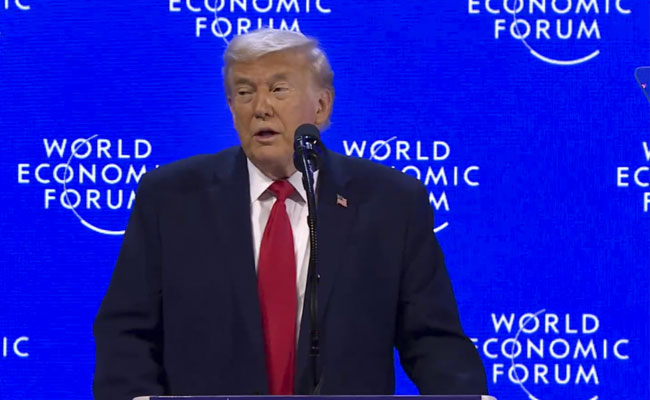

In the United States, where K-12 education is largely the responsibility of states and local school districts, President Donald Trump and his education secretary have urged schools to reopen in person.

But there has been heated public debate over the wisdom of bringing students back to the classroom, especially in communities with high daily new infections, so school reopening plans in the U.S. vary widely.

Most of the largest urban districts are starting the year remotely after a summer surge in virus cases. But other districts plan to offer face-to-face instruction at least part of the time. Some have already had to quarantine classrooms or shut down entire schools because of spreading COVID-19 infections.

AFRICA

Only six African countries have fully opened schools. In South Africa, students started returning to class this week class by class. It's the second time schools are reopening, after an initial reopening resulted in new infections and prompted new closures.

As daily COVID-19 cases are decreasing, the government has said all grades should be back in schools by Monday. The South African government has also allowed parents who don't want their children to return to school to apply for home schooling.

Elsewhere in Africa, Kenya has closed its schools for the rest of 2020. In Uganda, the government is procuring radios for rural villages to help poor families with remote learning.

JAPAN Some schools in Japan reopened Monday after a shorter-than-usual summer vacation to make up for missed classes earlier due to the pandemic. At an elementary school in Tokyo, mask-wearing children held a opening ceremony in classrooms instead of the school gym for better social distancing.

CHINA

As of last month, 208 million Chinese students, or roughly 75% of the country's total had returned to class, many on some type of staggered class schedule. The rest are expected to return by Sept. 1.

SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIA

Schools remain shut in India, Nepal and Bangladesh. In Sri Lanka, where the government says the virus has been contained to two clusters, schools were allowed to partially open this month for several grades facing government examinations shortly. Schools throughout Cambodia remain closed, while those in Thailand and Malaysia all reopened in July and August. Indonesian schools reopened in July with half-capacity classes and limited hours.

FRANCE

France is sending its 12.9 million students back to classrooms on Tuesday despite a sharp increase in infections in recent weeks. President Emmanuel Macron's government wants to bridge inequalities for children that were worsened by the coronavirus lockdown and get more parents back to work.

GERMANY Most German students are already back in school and at least 41 of Berlin's 825 schools have reported virus cases. Thousands of students have been quarantined around the country after outbreaks that some doctors attribute to family gatherings and travel during summer vacations.

BRITAIN Most of the U.K.'s 11 million students haven't seen a classroom since March, but children are to start returning to schools across England on Sept. 4. British Prime Minister Boris Johnson called reopening schools a moral duty, and his government even threatened to fine parents who keep their kids at home. Among measures in place are hand-washing stations and staggered starts and lunch times, but masks aren't generally required.

NORDIC COUNTRIES Most schools resumed class last week in the Nordics, as they did at the end of the spring term, amid a general consensus that there is more harm for kids staying home than the risk of sending them to school. Sweden has few virus measures other than banning parents from entering schools when they drop children off.

High school students even protested after Denmark's second-largest city shut their schools because of new infections, saying they don't learn as much remotely and questioning why they can go to shopping malls, gyms or the movies with lots of others but not school.

Let the Truth be known. If you read VB and like VB, please be a VB Supporter and Help us deliver the Truth to one and all.

After rapper and singer Santy Sharma's reaction to Khushi Mukherjee's provocative photo/video posts on social media, people on different platforms are now having a heated debate. The comments made by Santy were soon spread across social media and opened the door for conversations surrounding the type of content that is being posted by public figures on social media.

In his view, digital platforms provide a way to express themselves through creativity and art; however, he feels it is important for celebrities/influencers with a large number of followers to be mindful of how their content may be perceived by others. According to him, people who possess a large following online have a level of responsibility regarding the actions they display via their social media and should be cognizant of what type of example they are setting for the youth.

Lastly, creating art should inspire creativity as well as allow users to use their voices to support necessary change in society; therefore, creativity and expression through digital platforms should produce positive social change while still being aware of culture and society's expectations.

At the time of writing, Santy Sharma was discussing how online behaviour has contributed to increased rates of rapes, which stimulated much debate and debate online. Supporters have advocated for improved online etiquette, while others feel he was insensitive in his comments and contradicts the need for sensitivity on these sensitive issues. The controversy has gone beyond social media and increased debate regarding gender-based issues, the ethics of media influence, and the necessity to address serious crimes with appropriate awareness and sensitivity.

Meanwhile, Santy Sharma has also announced his upcoming single titled “I Don’t Care,” which is scheduled to release on 10 March 2026. The track will be available on his official YouTube channel and other major music streaming platforms, creating anticipation among fans who are eager to hear his latest musical release.